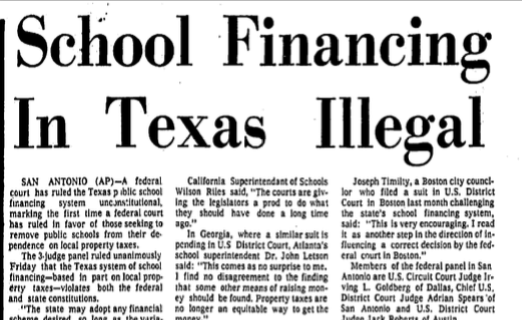

Edgewood v. Kirby main plaintiff, Demetrio Rodriguez surrounded by MALDEF attorneys Albert Kauffman (Left rear ) and Joaquin Avila (Right rear) in a photo taken shortly before Rodriguez, Kauffman and Avila walked to the courthouse and filed the case. Credit: (c) 1992 Alan Pogue.

MALDEF’S Landmark Fight for Education Equality in Texas

For years, low-income students in San Antonio were relegated to decrepit schools infested with bats—yes, bats—where tiles fell from classroom ceilings and underpaid teachers fled as soon as they could get hired elsewhere. These schools lacked funding for classes wealthier districts took for granted such as art and music. Basics such as math and reading in these schools were just that – extremely basic.

The fight to balance Texas’ public-school funding so that kids in poor districts – mostly Latinos – could get a chance at a decent education had been underway for several years when MALDEF (Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund) and its Senior Litigating Attorney Albert Kauffman joined the battle in 1984.

MALDEF filed suit challenging Texas’ methods of financing public schools. In the end, the case would change the way Texas public schools were funded and help narrow an historic educational achievement gap between rich and poor kids.

Filed on behalf of San Antonio’s Edgewood Independent School District, six other school districts and 25 families, the suit, known as Edgewood ISD v. Kirby, argued that Texas school funding violated the state constitution’s requirement that the legislature provide an efficient and free public school system.

“It really hurt them, and the parents knew it,” Kauffman says. “They had bad buildings, bad curriculum, inexperienced teachers, teachers on emergency certificates. They didn’t have as wide a curriculum, . . . and it bothered them.”

By contrast, wealthier – and whiter – districts such as Alamo Heights had gleaming buildings with pools and classes offering everything a child would need for a well-rounded education. They had buildings where art was made and classrooms where music filled the air. Rich districts, on average, collected eight times as much in property taxes and could spend two times as much per pupil than poor districts.

Texas journalist Roddy Stinson described the stark inequalities in a column after visiting a poor school that lacked a library, a gym, and other basic needed resources on San Antonio’s South Side.

“Our children are merely inconvenienced by not having a facility for physical education, but without reading resources and computer training, they fall further and further behind those students who have those ‘extras,’” the principal told Stinson.

Vast funding gaps between rich, white districts and poor, brown ones have been indefensible features of public school financing for generations, and they are not unique to Texas. In the 1940s, decades before MALDEF was founded in 1968, Latino parents fought to desegregate public schools in Orange County, California. Since 2012, MALDEF has been challenging New Mexico’s failure to adequately provide an education to low-income students – many of whom are Latino – and English-language learners.

In Texas, the inequities were stark enough to make the state a monument to educational discrimination.

“We filed the case because the students in poor districts, who were almost all Mexican American at the time, just didn’t have a decent education and people in other parts of the state did have a good education,” Kauffman said of the Edgewood suit. “And even though they paid higher taxes than the people in the rich districts, they still didn’t have nearly as much.”

The treatment of Mexican American students in Texas is an extension of that state’s history of brutal hostility toward Latinos. Between 1848 and 1928, for example, about 232 people of Mexican descent were lynched or killed— sometimes by Texas Rangers— lending a state sanction to some murders.

Texas was also known as an especially hard place for Latinos to exercise their right to vote, so much so that in 1975, MALDEF and others launched and won a fight to extend the Voting Rights Act to cover language minorities, and apply the VRA to Texas and other areas of Latino concentration.

Unequal school funding lasted for decades in Texas because of how the state legislature paid for public education. Texas allocated funds to public school districts for each student to get a minimum education. The districts could also use local property tax revenues to subsidize its schools, enabling wealthy districts to spend as much as $7,000 per student in 1984, while poor districts struggled to spend $2,000.

MALDEF was not the first to do a case like Edgewood, Kauffman said.

“There had been a federal case out of Texas before (and) there had been other state cases elsewhere,” he said. “But Texas was probably one of the worst examples of inequality, unfairness in the system. The facts were so bad that the case was fairly easy.”

MALDEF was not part of the 1968 federal suit Kauffman mentioned where 400 students, most of Mexican origin, walked out of Edgewood High School and marched to the San Antonio district office to demand school repairs and modern equipment such as electric typewriters, an overhauled curriculum and more qualified teachers.

The walkout inspired parents to create the Edgewood District Concerned Parents Association. One of those parents, Demetrio Rodriguez, was the namesake of Rodriguez v. San Antonio Independent School District (ISD), the federal suit filed a month after the walkout, challenging Texas’ school funding. Texas’ public school financing violated the U.S. Constitution’s equal protection clause, the suit alleged.

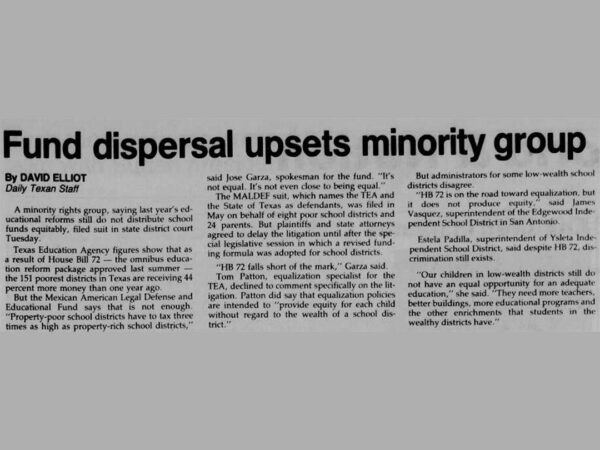

A unanimous three -judge federal district court panel agreed with the plaintiffs in Rodriguez, but the U.S. Supreme Court reversed that decision in 1973, ruling that the system was “unfair,” but not unconstitutional because there is no federal constitutional right to an education.

After the Supreme Court ruled against Rodriguez, the Texas legislature made some stabs at “equalization” reforms, but none bridged the wide economic gulf between affluent and poorer districts.

More than a decade passed before Demetrio Rodriguez would file a new challenge with MALDEF’s help. This time results would be different.

The Supreme Court had removed the possibility of another federal challenge by ruling that the Constitution didn’t guarantee a right to an education.

Kauffman and MALDEF had to find another way.

The solution was to attack the problem in Texas state courts. MALDEF argued in Edgewood that the state’s public school financing was racially discriminatory and violated the state constitution’s requirement to provide “equal distribution of knowledge” efficiently.

MALDEF’s strategy also went beyond the courtroom. Kauffman said MALDEF and its partners at Intercultural Development Research Associates (IDRA) went to the community to talk about school funding inequities, and “MALDEF lawyers and advocates were over in the legislature, pushing for good school finance.”

In 1984, Texas lawmakers passed a school-funding bill increasing state aid to poor schools by several hundred million dollars a year. But critics saw that bill (HB 72) as insufficient to keep up with the glaring discrepancies in per-pupil spending between rich and poor districts because it didn’t change the basic funding formula. Nearly a year after filing Edgewood, MALDEF amended its complaint to challenge HB 72 as “intolerably illegal.”

As the case made its way through the courts, more poor school districts, parents and students joined MALDEF’s challenge, increasing the plaintiff school districts from eight to 75.

Three years after filing Edgewood, Kauffman and MALDEF were in a Texas District Court in Austin arguing that the state’s formula for funding public schools helped trap poor districts in a cycle of poverty with no escape. Judge Harley Clark ruled in favor of the plaintiffs on April 29, 1987 and ordered the state legislature to find a solution by 1989.

Instead, Texas appealed.

The State Court of Appeals reversed Clark’s decision in 1988, adopting the U.S. Supreme Court’s position in Rodriguez that education is not a basic right.

The case landed before the Texas Supreme Court five years after it was filed. On Oct. 2, 1989, the justices held that Texas’ system of funding public schools violated the Texas Constitution’s provision requiring the state to maintain an “efficient” school system. Reliance on property taxes from wildly disparate tax bases built inequality into the system and must be changed, the court held.

The court said the state was “duty-bound” to provide an efficient system of education and gave the legislature until May 1, 1990 to find a solution.

In the following years, the legislature has passed various new funding bills, but those fell short and each attempt created new legal challenges to the funding formula. MALDEF has waged multiple lawsuits challenging the Texas school-financing system. As late as 2019, Edgewood ISD was still pinning its hopes on a new funding bill that would help its students. The work isn’t finished, but the 1989 decision in Edgewood v. Kirby laid the groundwork.

“That was probably the most important decision in the whole sequence,” Kauffman says, “because that was the first time that the Texas court had found that the Texas school finance system violated the Texas constitution.”

Edgewood v. Kirby Timeline

- May 16, 1968

- Jun 30, 1968

- Dec 23, 1971

- Mar 21, 1973

- May 23, 1984

- Jun 30, 1984

- Mar 5, 1985

- Sep 9, 1986

- Jan 20, 1987

- Jun 1, 1987

- Dec 15, 1988

- Oct 2, 1989

-

May 16, 1968

Hundreds students at Edgewood High School in San Antonio march to the San Antonio district administration office. Ninety percent of the students in the Edgewood School District are Mexican and Latino. Among the students’ grievances are insufficient supplies and the lack of qualified teachers. The walkout induces parents to form the Edgewood District Concerned Parents Association to address problems in the schools. The group consists of Demetrio Rodríguez, and other parents, mostly mothers.

-

June 30, 1968

Edgewood District Concerned Parents Association files a federal lawsuit in the District Court for the Western District of Texas. The suit, known as Rodriguez v. San Antonio Independent School District, challenges the state’s method of school financing as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution.

-

March 21, 1973

The U.S. Supreme Court reverses the three-judge district court’s decision, concluding that while Texas’ school finance system is unfair, it is not unconstitutional.

-

May 23, 1984

MALDEF files a state lawsuit against Travis County Commissioner of Education William Kirby on behalf of the Edgewood Independent School District in San Antonio. The lawsuit, known as Edgewood v. Kirby, challenges the inequitable resource allocation in Texas public schools as a violation of the state constitution, which requires lawmakers to provide an efficient and free public school system. Initially, eight school districts and twenty-one parents are represented in the Edgewood case. Ultimately, however, sixty-seven other school districts as well as many other parents and students join the lawsuit.

-

Oct. 2, 1989

The Texas Supreme Court rules unanimously that the state’s school finance system is unconstitutional, reversing the appeals court decision and affirming the district court’s decision for plaintiffs. The court also gives the state legislature until May 1990 to produce a new school-funding system to remedy the inequities.