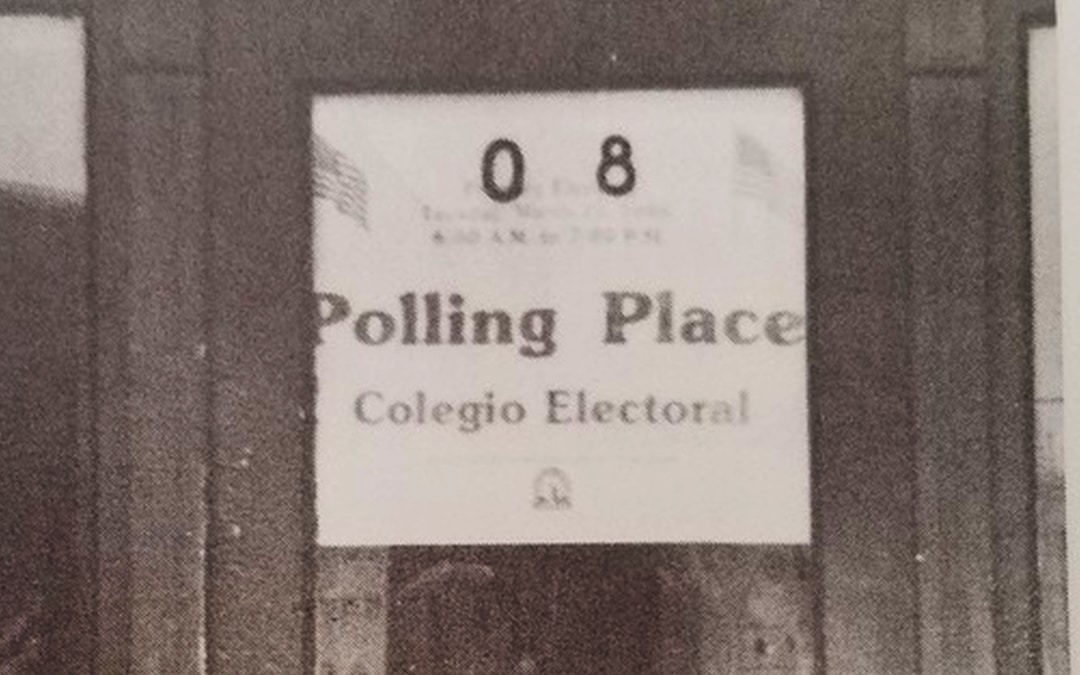

Bilingual ballot from a California local election in 1976, nine months after the 1975 amendments to the Voting Rights Act were enacted.

MALDEF Successfully Pushed to Expand the Voting Rights Act to Language Minorities

In Uvalde County, Texas, the political atmosphere of 1975 was such that election officials routinely ran out of registration application cards when Latino applicants asked for them. And tough luck for voters who could not read English because election judges refused to assist them.

What occurred in Uvalde County existed all over Texas, said Vilma S. Martinez, then MALDEF president and general counsel. She told a congressional subcommittee that the abuses aimed at keeping Latino voters away from the ballot box were so pervasive, it was impossible to guarantee them a meaningful right to vote through individual private litigation only.

“It would be like attempting to empty the sea with a sand pail,” Martinez said.

She was testifying because MALDEF was leading the push to expand the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to protect Latino voters and to require that ballots and election materials be provided in Spanish and in the languages of other racial minorities.

In 1974, MALDEF’s Washington D.C. Counsel, Al I. Perez, decided to seek changes to the VRA after learning from a friend at the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights that, despite receiving considerable testimony about voting rights violations against Mexican Americans, the commission refused to support amending the Act the following year to address violations like those in Uvalde County and elsewhere.

Needing assistance, Perez recruited pro bono lawyers David Tatel and Thomas Reston of Hogan & Hartson, a Washington, D.C. law firm. Together the three formulated a legal, legislative, media and community outreach strategy of proposed amendments to the VRA’s preclearance provisions to include areas with significant numbers of certain language minorities.

Expanding the Voting Rights Act was but the latest effort Latinos had made to overcome voter suppression. In 1971, MALDEF and other groups decided to challenge electoral districts in Texas that diluted the Mexican American vote by creating supersized white-majority mega- districts with several elected representatives.

In a case called White v. Regester, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Texas’ urban voting district in Bexar County, which covered more than 1,000 square miles and included nearly one million people, was unconstitutional because it diluted the Mexican American vote, which was concentrated in the Westside of San Antonio, and reduced Latino representation in the Texas House of Representatives.

The plight of Latino voters sounded familiar to some members of Congress. During debate on the 1965 Voting Rights Act, many of them had heard similar stories of corrupt political leaders, mainly in the South, and their criminal accomplices willing to embrace any perverse measure to maintain their power – literacy tests, poll taxes, economic retaliation, abductions, beatings, murder.

Just as African Americans had before them, Latinos had to overcome a litany of abuses, among them gerrymandering, mega districts, English-only election materials, at-large elections, closed polling places.

Ninety-five years after the 15th Amendment was supposed to bar racial discrimination at polling places, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, in part, to combat the legacy of lawless conduct Southern officials had established in their determination to deny voting rights to black Americans.

The impact was immediate. Within months of the law’s passage, 250,000 new black voters had been registered in the South, and 1.5 million new black voters were registered in the following decade.

But those gains were not shared by Americans of Latino descent.

“Despite the presence of the 14th and the 15th amendments, this country has seriously failed to protect the voting rights of over 12 million Spanish-speaking citizens,” the late Edward R. Roybal, then a member of Congress from Los Angeles, told the subcommittee. He cited an incident in California where an election official insisted that people who do not speak English should not have a right to vote. “If the Spanish people do not speak English, they should be kicked back into Mexico and not be allowed to come back,” the official said.

In another town, an election official told a woman helping a Spanish-speaking voter that if “the woman wanted to vote, she should know how to speak English.”

In 1975, Roybal and his House colleagues, Herman Badillo of the Bronx and Barbara Jordan of Houston, introduced legislation requiring bilingual election materials in areas where Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans or Alaskan natives made up more than 5 percent of the voting-age population.

The bill also forced areas to have any changes in their laws approved by the federal government if less than 50 percent of eligible voters had registered or voted in the 1972 election. That provision meant Texas, which was not covered under the 1965 act, would now be subject to U.S. Justice Department “preclearance” before it could change its election laws.

“There has been a great failure on the part of the state of Texas to protect the voting rights of the Chicano electorate,” Modesto Rodriguez, a farmer and political activist, testified. “For the protection of our voting rights we are now relying on the Congress and more specifically on this subcommittee to act to extend federal protection of the right to vote to the 9 million Spanish-speaking citizens of this country.

“Democracy does not come easily and we are asking for your help in this matter.”

He described how police brandished guns and intimidated voters in Latino precincts, and how one man asked an “Anglo lady who was taking down the names and photographing Mexican American voters to stop because she was intimidating the voters.”

The next day on his way to church, Rodriguez said, that man was arrested and charged with assault and battery, burglary, disorderly conduct and disturbing the peace. After looking at the all-white jury, Rodriguez said, the man decided he didn’t have a chance, pleaded guilty, and was fined $238.

Rodriguez himself was the victim of police violence when he was recruiting witnesses to testify before congress on election abuses in Texas. An officer struck him in the head with a heavy flashlight before joining other officers in kicking and beating him, puncturing an ear drum and causing permanent hearing loss in one ear.

MALDEF faced opposition from Clarence Mitchell, head of the NAACP’s Washington D.C. bureau and legislative chairman of The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, who worried that expanding the Voting Rights Act might “improve it out of existence.” Congress, with dogged lobbying by Latinos, voted to expand the act after hearing from activists like Rodriguez and leaders like Martinez.

The expanded law made a difference right away. The Justice Department stopped a massive voter purge in Texas, local Latino elected officials in Texas increased by more than 200 over the next decade, and courts forced local governments to adopt districts that fairly represent Mexican Americans. Latino members of Congress from the Southwest rose from one to nine over the next decade, and city councils in Los Angeles, New York and Chicago saw increases in their Latino members.

But the battle for the ballot was by no means ended.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder that the formula used to decide which states were subject to preclearance was unconstitutional. Within days of the decision, Pasadena, Texas Mayor Johnny Isbell tried to change local elections with a system designed to protect white control of the city council, even as the Latino population was growing rapidly.

The change eliminated one Latino-majority district and imposed a combination of at-large and district elections that prevented Latino-backed candidates from winning a city council majority.

Isbell’s reason for pursuing the change: “Because the Justice Department can no longer tell us what to do.”

But Isbell was stopped.

MALDEF sued and won a federal court ruling that Pasadena intentionally sought to dilute Latinos’ voting strength. The court ordered the city to obtain preclearance for its election law changes from the Justice Department, the first ruling by a federal court ordering preclearance after the Shelby County decision.

The right of minorities to vote remains under attack with draconian voter ID laws, shortened voting hours, illegal purging of voter rolls, and relocated or closed polling places. Those attacks on the right to vote are nothing short of an attack on democracy itself.

As Roybal testified before the Senate subcommittee, the right of the people to cast a meaningful and effective vote “goes to the very democratic roots of this country. The preservation of this right is important to the vitality of this country’s political system. It’s denial, it’s enfeeblement, can only jeopardize our commitment to democratic principles.”

“The struggle waged by MALDEF to ensure that the Voting Rights Act protects Latino voters is unfortunately emblematic of the ongoing struggle to secure civil rights laws that will protect the rights of all, including addressing rights denied to Latinos through their particular experience of entrenched discrimination in our country,” said Thomas A. Saenz, MALDEF’s current president and general counsel.

Voting Rights Act Timeline

[extlsc id=”34506″]