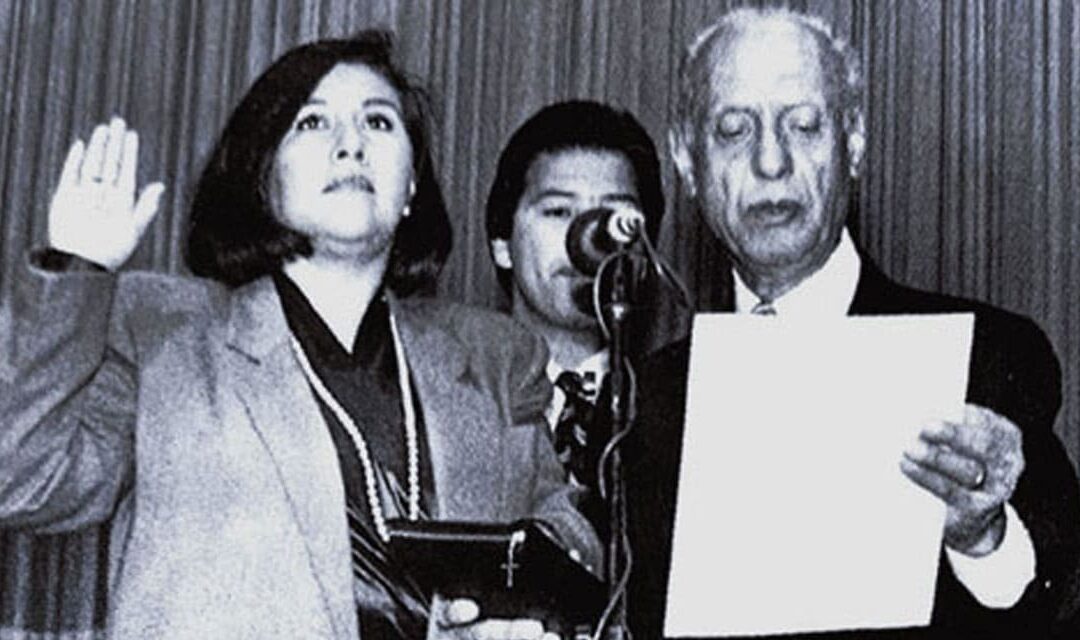

Gloria Molina was sworn in on March 3, 1991, as Los Angeles County Supervisor.

MALDEF Lawsuit Created First Latino-Majority Seat on Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors

For years, the white men who always managed to win election to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors were called the “Five Little Kings.” Even as the Latino population continued to grow, the revolving door of white supervisors continued the same as it had since the current county boundaries were drawn in 1885.

It took a voting rights lawsuit by MALDEF and others called Yolanda Garza v. County of Los Angeles and a Supreme Court rebuff to force the board to accept its first Latino-majority district in over a century in a county now with a population greater than 10 million – more than 43 of the 50 states.

Gloria Molina, who won election to the new district in 1991, said her work on the lawsuit as a volunteer activist and researcher “was amazing” and “exciting.”

“But at the same time frightening,” Molina said, because if the suit failed, county services in what became her district would have remained poor or nonexistent. “If in fact we couldn’t win this, then it was clear that these operations were going to continue to discriminate,” she said.

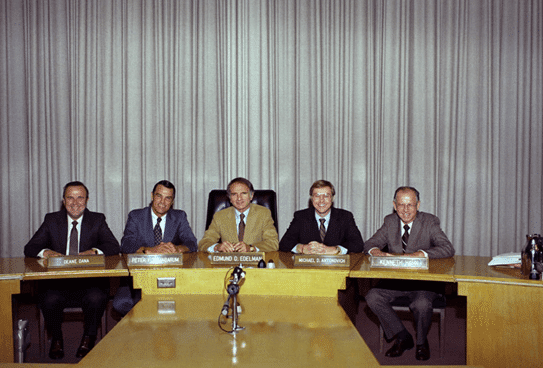

Fed up with decades of gerrymandering, MALDEF sued the board in 1988 on behalf of Garza and four other Latino voters. MALDEF argued that the board’s three conservative Republicans – Peter F. Schabarum, Deane Dana, and Michael D. Antonovich – and its two Democrats – Kenneth Hahn and Edmund D. Edelman – violated the U.S. Voting Rights Act by voting unanimously to reject a Latino-majority district in 1981.

The board intentionally violated the Voting Rights Act, MALDEF said, by repeatedly dividing Latino neighborhoods in East Los Angeles and the San Gabriel Valley, known as the Hispanic Core, whose 1.2 million population at the time was over 70 percent Latino.

After a three-month trial, U.S. District Court Judge David V. Kenyon agreed.

The Latino community “has sadly been denied an equal opportunity to participate in the political process and to elect candidates of their choice to the Board of Supervisors for this burgeoning county,” Kenyon wrote in his June 4, 1990 decision. The board “appeared to ignore the three proposed plans which provided for a bare Hispanic population majority” and instead adopted a 1981 district map that “continued to split the Hispanic Core almost in half,” the judge said.

Kenyon, appointed by President Jimmy Carter, concluded that the board engaged in intentional discrimination against Latino residents by drawing district boundaries to preserve the white board members’ supremacy – not just once, but also in 1959, 1965, 1971, and 1981.

During the trial, Supervisor Schabarum didn’t help his side by testifying that it was “fundamentally un-American and unsound” to fashion district lines with the intent of permitting ethnic groups to be represented.

MALDEF’s lawsuit also uncovered secret board documents and meetings. One memo revealed a plan to shift a group of “lily white” voters into a white supervisor’s district to prevent a Latino majority. MALDEF also discovered that the board had met secretly on September 24, 1981 to draw a new map preserving the status quo, and then voted 5-0 in public session to adopt the secret map, even though it had never been shown to the public or discussed in public.

Kenyon ordered a new county map, creating a new First District in the Hispanic Core. The judge’s ruling would produce far-reaching changes in a county with a long history of official discrimination that included restrictive real estate covenants, segregated public schools, and the repatriation of Latino residents, including the forced expulsion of U.S. citizens, to Mexico.

The board refused to accept Kenyon’s ruling and his map and appealed. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected the county’s appeal and issued a ruling on Nov. 2, 1990 approving the new district and Kenyon’s finding of intentional discrimination.

Once again, the board refused to accept a court decision, and asked the U.S. Supreme Court to take up the case. But the High Court issued a one-sentence denial on January 7, 1991. Unable to stall any longer, the county held a special election on February 19, 1991 for the new First District.

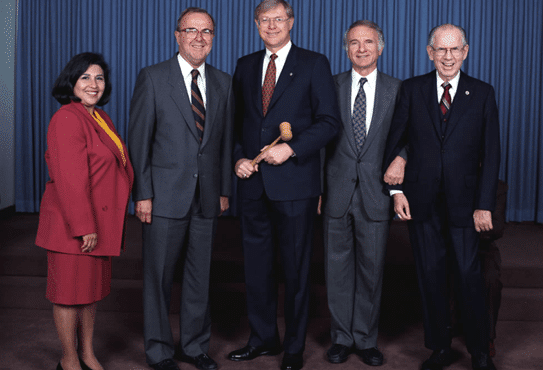

Molina won, beating 12 other candidates, including her old boss, then-state Sen. Art Torres. She was the first woman and first Latina supervisor elected, breaking more than a century of the board operating as what amounted to an exclusive club for white males. Her election flipped the board from majority conservative to majority progressive for the first time in years.

When all of the legal costs the county ran up fighting the MALDEF suit were tallied, Los Angeles County taxpayers were hit with a $12.8 million tab.

Molina watched – but could not vote – as her colleagues reluctantly voted to pay those millions in attorney’s fees to MALDEF and other organizations, including the ACLU and the U.S. Justice Department, which also filed suit against the county.

“I just sat there beaming,” she said. “They had just lost the lawsuit. And then they had to pay.”

Once in office, she had to do battle with county bureaucrats and the sheriff’s department to end years of neglect in her district, then the county’s stepchild where basic services were concerned.

“I had the dirtiest streets,” she said. “I had trash that wasn’t picked up. They just weren’t cleaning the streets even though they said they were.” There was a lot of crime, she said, but “law enforcement cars weren’t showing up.”

She went out into her district at night and called the sheriff at 2 a.m. to demand more patrol cars on the streets. She also demanded new street sweepers to replace the broken ones dumped in her district.

For Molina, the opposition to her candidacy was a clear example of an unwillingness to recognize the Latino community’s growing influence. “It all has to deal with the sharing of power, which is what redistricting is all about. They just don’t want to share the power.”

The Garza Case Timeline

- 1981

- Sep 24, 1981

- Aug 24, 1988

- Sep 8, 1988

- Oct 4, 1988

- Jul 28, 1989

- Aug 9, 1989

- Jan 2, 1990

- Apr 10, 1990

- Jun 4, 1990

- July 1990

- Aug 3, 1990

- Aug 6, 1990

- Nov 2, 1990

- Jan 7, 1991

- Feb 19, 1991

- May 1991

-

1981

The 1980 U.S. Census shows that 27.6 percent of Los Angeles County’s total population is Latino, the vast majority of whom live in the eastern part of the City of Los Angeles — dubbed the Hispanic Core. More than 67 percent of the Hispanic Core population is of voting age.

-

August 24, 1988

MALDEF sues the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors on behalf of Yolanda Garza and four other Latino voters in Los Angeles County. The federal lawsuit, filed alongside the ACLU of Southern California, challenges the 1981 redistricting map because it violates the federal Voting Rights Act (VRA) and the Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The plaintiffs demand a new voting map be drawn to include a majority-Latino district in time for the 1990 election. Their lawsuit is Yolanda Garza v. County of Los Angeles.

-

July 28, 1989

The Justice Department files a motion to compel the supervisors and their staff to testify about the board’s secret September 24,1981 meeting to create and approve a redistricting map. The request follows the supervisors’ refusal to testify during depositions, claiming the information is protected by the deliberative privilege.

-

August 9, 1989

U.S. Magistrate Judge Charles F. Eick grants the Justice Department’s motion to compel the supervisors and their staff to testify about their secret meeting regarding the district map, holding that even though they were protected by the deliberative privilege, the need for the information overcame any privilege. United States v. Irvin (127 F.R.D. 169 (C.D. Cal. Aug. 9, 1989).

-

January 2, 1990

Trial begins before U.S. District Judge David Kenyon. Attorneys for the county argue that the districting map should not count non-citizen Latinos and Latinos who are too young to vote. During the three month trial, Supervisor Pete Schabarum testifies that he thinks it is “fundamentally un-American and unsound” to fashion district lines with the intent of permitting ethnic groups to be represented,” Judge Kenyon notes in his later opinion.

-

June 4, 1990

Judge Kenyon rules that the Board of Supervisors intentionally discriminated against Latino voters in the 1981 district map. The court finds that the 1981 map violates the VRA and the Fourteenth Amendment by cutting “the Hispanic Core almost in half” and diluting the strength of the Latino vote. The judge rejects the county’s argument that voting district maps should not count non-citizens and people too young to vote, saying both California law and the Supreme Court concluded that voting districts should be based on the “population” numbers, not voting status. The judge orders the board to redraw the map with a Latino population majority and submit it for his approval.

-

November 2, 1990

Ninth Circuit affirms the district court’s ruling and the new map with a Latino-majority district.

-

February 19, 1991

Los Angeles County holds a special election to fill District 1, which became open after Supervisor Pete Schabarum decided not to run for reelection in the new Latino-majority district. Schabarum agrees to stay in office until the special election is held. Los Angeles City Councilwoman Gloria Molina is elected to District 1 of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, the new Latino Majority district.